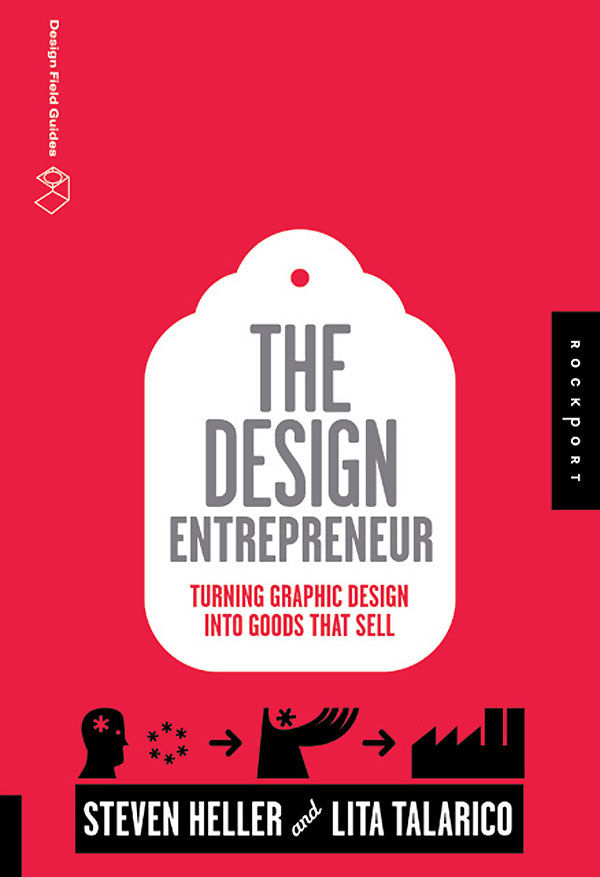

The Design Entrepreneur – Turning Graphic Design into Goods that Sell

Article by Martin Gibson – @embody3d @martingibson – 01.05.2011

The Design Entrepreneur – Turning Graphic Design into Goods that Sell, by Steven Heller and Lita Talarico and published by Rockport reveals a growing trend amongst graphic and product designers who are stepping away from typical designer-client projects to developing their very own products that sell.

There probably is a trend in this direction, but the authors make this assumption without any statistical evidence behind it. Of course I am not saying that every claim has to be backed up, but this is a pretty huge assumption and a recurring theme throughout. This is certainly not a trend participated by all designers, nor is there anything new about these freelance turn product development entrepreneurs. As even before the most notable 19th century textile designer William Morris, many designers and artists have ventured into the product development space. Perhaps this recent spur of entrepreneurial activity has arisen by necessity rather than choice due to loss of jobs from the Global Financial Crisis and outsourced and globalised manufacturing. As I have heard many say in America recently, if there are no jobs around, well create your own job.

The Design Entrepreneur is split up into two sections:

- An introduction to the topic area citing a few examples of successful product developments and a general explanation/theoretical lesson about how to conceive clever design ideas. This is then followed by practical advice on how to develop, market, protect, distribute and pitch these design ideas.

- This is then followed by a long series of interviews, 53 in all (wow), of successful designers and studios who have developed their own product ranges.

1. The Background, Research and Advice

The introduction of The Design Entrepreneur is a painful experience. It is over-simplified most likely targeted to a mid high school audience and once again makes these wild assumptions. Let me give you one for example:

“Designers have traditionally been brought in at the end, rather than the beginning, of a product (certainly after the fundamental decisions are made) and hired to package, rather than conceive.”

Have they really? I am sure you would agree this has never happened, even in the last 200 years. I think the authors here are getting confused with different industries and different cultures and structures of design. Take for instance in Europe they have a very fragmented design development process, where for example in the automotive industry a design engineer will develop the base of the chassis and this would then be followed by a conceptual designer who will define the aesthetic details. But throughout history there have been many designers and participants amongst the arts and crafts movement that have designed products without precondition or interference, this statement is just plain misguided.

The other aim of this introduction is to add excitement and spur graphic designers on to venture into this space. But it does so in such a remedial manner. For example there is a full-page diagram showing the recipe of success for the design entrepreneur and it illustrates two scientific beakers pouring into a blob mans brain with one beaker titled ‘will’ and the other ‘intelligence’. This kind of over-simplified mantra conditions the reader superbly for the remaining contents of the book.

The next chapter on ‘Conceiving Ideas’ (the most successful of all the chapters in The Design Entrepreneur) gives the audience a blossom of hope as it details how the 1950’s was the era of the ‘Big Idea’ and how ideas didn’t have to just look great, but had to function supremely hence raising the quality standards of consumer products. It is unfortunate that this outline isn’t exemplified in the half century interviews to follow. Despite this, the chapter contains some cool projects that describes the designs purpose, back story and aesthetic design. Some designs include some cute and funky clocks designed by Rick Landers, and some minimalist bowls with a small flair of colour by Jennifer Panepinto.

The remaining chapter of this first section ‘From Idea to Product’ gives some more practical advice on how to turn your great idea into a product reality by briefly outlining some pointers about testing your products viability, understanding marketing and promotion, and protecting and distributing your product. This section gives a good starting point into these core considerations, but realistically these small paragraph explanations are of little practical value as a dozen books could easily (and is) dedicated to these specific areas alone. However what can’t be forgiven in this chapter is the incorrect advice detailed in the intellectual property section. I appreciate that the authors have decided to supply these headings with just a few paragraphs of information, but in the intellectual property section they have confused the protection required for the types of projects they have been illustrating. For some reason the authors are saying that the strongest protection for your product is a © symbol which protects all works under The Copyright Act. This is all well in good for graphic design projects, but for product design projects there are a completely different set of rules. For products one can use Trademarks and Design Registrations to protect the look of the product, and one can also use patents and innovation patents to protect the inventive and novel aspects of a product. If one was to ask any product designer it would almost be a crime to suggest in developing products to use © symbols to protect the work, it would give you absolutely no protection whatsoever.

From the very beginning The Design Entrepreneur seems to confuse the idea of what is a graphic design and what is a product design. Granted there is a fuzzy line between the two as both involve designers who define the visual elements of shape and colour of the end product. Although it is much debated I see the difference between these fields as graphic designers utilising a 2D/2.5D canvas, whereas product design builds upon a full 3D canvas. Of course there are overlaps like for example: who should design a mouse pad or a simple shopping bag? A graphic or industrial designer? That’s a tough one, but of course it depends on the skillset of the individual designer at hand. But where this book goes unfortunately wrong is in its design approach for transitioning existing graphic designers into the 3 dimensional space. Let me explain using the previous: who should design a mouse pad example. Ask a graphic designer to design a mouse pad and without trying to stereotype too much, they would likely think about the colour and design of the print of the mouse pad and then would just get it printed. However, if one were to give a product or industrial designer the same task, one would expect a more overall approach to the design. An industrial designer might say…”hey how can we improve the ergonomics of a mouse pad..what cool new materials could we use to make a mouse slide better? What shape makes the most sense (for example why do mouse pads have a 4:3 aspect ratio when most screens now are 16:9)? Maybe we could actually make it one giant tablet or touch pad like a graphics tablet. So instead of having just a standard but beautiful looking mouse pad, a product designer might end up conceiving a whole new interface for interacting with a computer. I hope you see this different frame of reference to the same design problem. Even through all the great interviews that are to follow, the designs are absolutely littered with examples of this stifled approach. Designs that in some instances just slap a cool graphic design onto a plate, a t-shirt, a bag or a figurine and label them as a design success story. When in reality this cool design slap on approach is a market that is extremely competitive and a market that is over-saturated. Besides, hasn’t anyone heard of Zazzle.com?

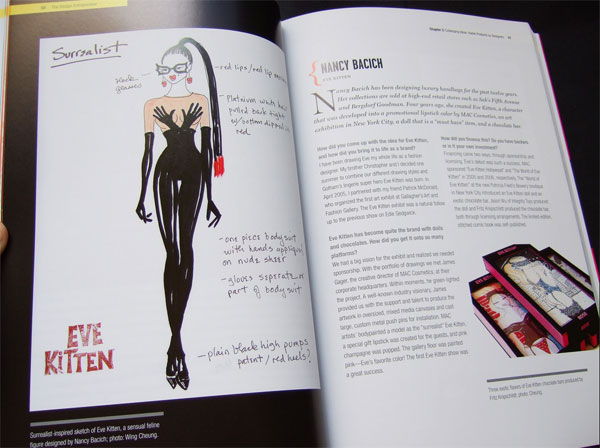

2. The Interviews

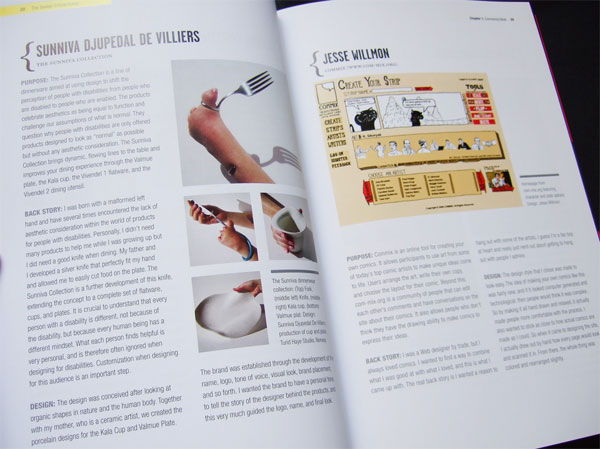

The majority of the book is filled with interviews, and this is a real positive to take from The Design Entrepreneur and potentially makes up for the misgivings I had about the initial part of the book. The interviews provide some helpful insight to graphic designers as to some of the challenges of developing products and the tools and methods that can be utilised to create, promote and distribute them. I am not going to get into too much specific detail about the interviews because there are quite frankly way too many of them, but I can say that the high-caliber interviewees some include: Dave Eggers, Maira Kalman, Charles Spencer Anderson, Seymour Chwast, Jet Mous, Nicholas Callaway and Jordi Duro are very honest and forthcoming to giving advice which makes the interviews a joy to read. The pictures of the designs are well portrayed and unlike many other books they are well captioned as well. Through sheer quantity, the interviews provide a tonne of inspiration of the types of projects prospective graphic designers might like to get into, from packaging to clothing.

However as I have emphasised previously these interviews probably go a little too long and it makes the questions despite being unique seem somewhat repetitive. It is a shame more space wasn’t allocated to the initial part of the book where more detailed practical advice would have been welcomed.

In Conclusion

I feel like I am perhaps being a little to nit picky with this book, but there are just so many things to nit pick at. From the very get go to the absolute end The Design Entrepreneur delves into a real grey area of what is graphic design and what is product design and it never quite points out the difference. Consequently this makes the design waters murky, and in doing so it indoctrinates this small-minded graphic design approach to product design problems.

The Design Entrepreneur paints a very rosy picture about this apparent growing contractor gone freelance trend; if you have talent and the motivation and persistence to succeed you will, just like all the great designers we have interviewed. I feel that many talented graphic designers will follow this books example and find themselves in a saturated and valueless market. Where only few succeed, and these few will have found themselves in these privileged positions through opportunity at times rather than skill. The book makes its most insightful comment in the ‘Conceiving Ideas’ section in relation to the 1950’s design movement:

“It was certainly a coming-of-age period of American consumerism and prosperity, when advertising and design were more than the process of making things look good. The result had to sound, read, and look smart. Indeed, smart ideas were supreme, and everything else was merely fluff.”

Unfortunately this great insight is never fully developed on and the resulting designs sometimes feel a little fluffy.

The Design Entrepreneur serves as a great way to inspire and motivate the eager graphic designer, but unfortunately as a way of education and practical advice the book is directed at a high school audience which I think despite it’s very best intentions, it doesn’t want to achieve. On the high note is the interviews, and their great first hand advice and long tally of brilliant designs. I think the idea of this book is really fascinating, and there is a huge market of graphic designers who are curious about developing their own products, but the execution of The Design Entrepreneur is by no means perfect.

[rating:2]