Article by Sarah-Jayne McCreath as part of the E3D Industrial Design Writing Competition – @embody3d – 13.09.2010

Character of Character by Sarah-Jayne McCreath

The article The Character of Things by Lars-Erik Janlert and Erik Stolterman proposes the philosophical idea of character inherent in objects, the process in which character can be employed as a conceptual device and the possible consequences for its use in design. In this piece, I propose that the user or person perceiving an object is solely responsible for assigning any meaningful character to it. Although steps can be taken to design character into the object due to sensory experience, character is entirely subjective according to the userʼs own unique character.

A background on character

The word character can be defined in many ways depending on the context in which it is being employed. In the article The Character of Things, Lars-Erik Janlert and Erik Stolterman define character as “a unity of characteristics”. Their philosophical investigation of the term takes its cues from both the definition used in drama and the definition used in personality psychology. Character can be broken down into characteristics that Janlert and Stolterman define as groups of attributes an individual possesses that collectively relate to each other to form the whole character.

These characteristics are further modified by an individualʼs mood. These moods exaggerate or diminish the true characteristic inherent in the individual. For example, some people seem light hearted by character, whilst some are light hearted only in passing according to their mood. Hence, an individualʼs character is better known if you have time to become accustomed to their genuine characteristics as opposed to their passing moods. Knowing someoneʼs character can lead you to predict what that individual will do and in what manner they will do it. If you know from experience how an individual will react to a certain situation, you can safely predict how they will react to similar situations in the future.

This process of interpersonal perception develops over time from interaction between two people. In The Character of Things, Janlert and Stolterman discuss similarities between associating character to people and associating character to things. They look at influential social psychologist Edward E. Jonesʼ attribution process, which is a psychological theory of interpersonal perception. It consists of the perceiver, situation and target person and the expectancies that occur in different stages of interaction between them. This model can also be applied to the study of character in objects.

Character in objects

“People have a habit of thinking and talking of artifacts as having character, as a way of understanding them and remembering how to handle them” – Janlert and Stolterman. A person often ascribes character to objects subconsciously. It is not to say that they actually believe that the object has a conscious personality, rather it is a tool they apply to a complex object in order to handle its reality and predict its behaviour and functions.

However, even though a complex object may be assigned a character by its user, it does not mean that the user isnʼt knowledgeable when it comes to the objects complexities. According to Janlert and Stolterman, expert users of computer artifacts tend to apply advanced character to their machines. This could be due to the tendency of computer design to be anthropomorphic in form or, to the intensive and extended relationship that the user develops with the object.

When a person ascribes character to an object, it is not only formed by their visual perception of the object; it is the result of a sensory experience. When a person hears the roar of an engine, they will assign character to the vehicle based on its sound. All the senses help a user to form a character for the object that they can relate to and respond to appropriately. “The attribution of character to an artifact can also be based on its style of conduct, the way it moves, the way it performs its tasks, the way it reacts to your touch…” – Janlert and Stolterman. When a user feels the weight of a pen in their hand, it will assist them in forming an overall sense of the penʼs character.

The process of character perception in objects

Looking at the way people perceive character in each other is helpful in determining how people perceive character in objects. The Attribution Process theory of E.E. Jones outlined in The Character of Things gives us a model for interpersonal perception between people. This model can be adapted to objects and used to determine what expectations the perceiver has in regards to an objectʼs behaviour.

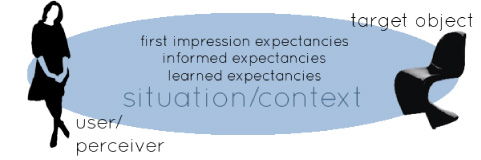

Adapted by author from Interpersonal Perception (Jones, E.E. 1990)

The process of character attribution to an object can be broken down into three categories.

– First impression expectancies, called category based expectancies by Jones, are characteristics the perceiver attributes to the object early on in the interpersonal perception timeline. These attributions are determined by the initial appearance of the object (the sensory experience) and stereotypes (if the object is part of a well known group). In laymenʼs terms it can be equated with “judging a book by its cover”.

– Informed expectancies, called target based expectancies by Jones, are characteristics the perceiver attributes to the object after intermediate interaction with it. The perceiver getting to know the object better and taking aboard the opinions of others determines these attributions. Their expectations of the objects behaviour are tailored to suit their acquired knowledge.

– Learned expectancies, called normative expectancies by Jones, occur when the perceiver gains familiarity with the objectʼs functions and its system of use. This stage of the attribution process is the time when the user is most familiar with an objectʼs character as a whole.

Because the situation or context that this attribution process occurs within “sets limits on the possible behaviour of the target [object] and the perceiver” – Janlert and Stolterman, the inherent character, personality and/or preferences of the perceiver themselves also set limits on the scope and description of the character that they assign to the target object.

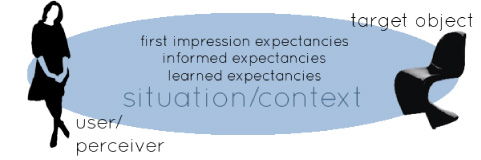

Adapted by author from Interpersonal Perception (Jones, E.E. 1990)

The process of character attribution to an object can be broken down into three categories.

– First impression expectancies, called category based expectancies by Jones, are characteristics the perceiver attributes to the object early on in the interpersonal perception timeline. These attributions are determined by the initial appearance of the object (the sensory experience) and stereotypes (if the object is part of a well known group). In laymenʼs terms it can be equated with “judging a book by its cover”.

– Informed expectancies, called target based expectancies by Jones, are characteristics the perceiver attributes to the object after intermediate interaction with it. The perceiver getting to know the object better and taking aboard the opinions of others determines these attributions. Their expectations of the objects behaviour are tailored to suit their acquired knowledge.

– Learned expectancies, called normative expectancies by Jones, occur when the perceiver gains familiarity with the objectʼs functions and its system of use. This stage of the attribution process is the time when the user is most familiar with an objectʼs character as a whole.

Because the situation or context that this attribution process occurs within “sets limits on the possible behaviour of the target [object] and the perceiver” – Janlert and Stolterman, the inherent character, personality and/or preferences of the perceiver themselves also set limits on the scope and description of the character that they assign to the target object.

Consequences for design

Janlert and Stolterman argue that consistency is the key to ensuring character is considered and included in the design process. This is not to say, consistency as uniformity of functions and use, as “in the everyday world people tend to get bored by too much uniformity and consistency; these are standards that fit machines better than human beings.” Rather a consistency of character means that the object should embody a “coherent unity of characteristics… that applies across different functions and qualities of the [object]”. For example, the rate in which files open in a computer interface or files are deleted should be discernible from each other by their speed. This speed then becomes a characteristic of the interface.

While I agree that characteristics can be embodied in the design from the conceptual stage, it is also good to note that meaningful character (that which is meaningful to the perceiver) is something that can only be applied by the perceiver over an extended period of interaction.

From Jonesʼ attribution process it can be seen that the perceiver governs a lot of the attribution process him or herself. Although a designer can manipulate elements of the design of an object; feel, visual aesthetics, sound, weight, scent, anthropomorphism, semantics, embedded metaphors and the like; it can be surmised that the character of an object is largely dependent on the interpersonal, or perceiver-object, relationship that evolves over time.

This perceiver-object relationship is subjective because of the role of the perceiver. Each perceiver is unique, no matter their type or group, whilst the object is static. The perceiver possesses an individual worldview or lens that they observe their environment through. Even though an object has a set system of functions and possibilities of use, it is evident in common situations that different individuals manipulate the same objects in different ways. These perceiver driven manipulations of functions and use determine character in an object that is meaningful to the perceiver.