TJJ Q and A

You’ve won numerous awards for your design work over the years. Is it important that industrial designers get the same kind of praise as other artists for their creations?

I think it’s more important for the client than the designer. The clients use it for commercial purposes, they say ‘buy this product because it won this award’. You assume it’s going to impress somebody, and it impresses certain clients.

It’s nice that design has gotten more acknowledged in the last 25 or 50 years so that’s important, but for me as an individual, it’s not too important. It’s important for the design world in general and it’s a good initiative that they give these out, and they try to give it to products that make this world better, so in the global respect I guess its good.

Given your family background, were you always likely to be product designer or did you ever consider any other design fields?

I was so young. I’m the youngest of the first bunch of kids. Being the youngest you make more noise to get heard and I always invented stuff since I was three or four, so maybe I had that in my genes that I wanted to create. I was just a 16 year old just thinking of next Friday and the girls, and dad said I’ll give you £10 a day if you show up in the studio from 8am and don’t leave until 4pm. That’s how it started and it just worked out, for him, for me, for us, and the rest is history.

You collaborated with your father for some of your early work for, among others, B&O. How did working with him effect your own style, both in terms of design and work ethic.

Because I grew up with it and the studio was in the same building as we lived, when my siblings went to school I’d be at home with my mum and I’d go to the studio and hang out. It was just my world.

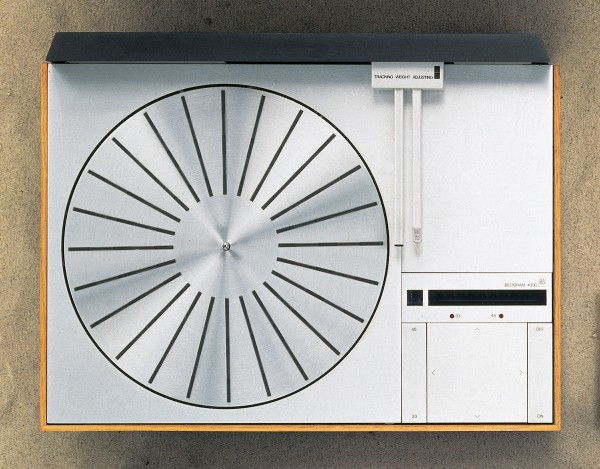

I guess if you had to say there’s a difference between what he made and we make now, I think if you look, for example, at a BeoGram 4000 turntable, it’s nearly graphics, it’s hardly 3D. It’s really beautiful. And I think you could say we made the Jacob Jensen form language more three dimensional than in his days.

I was reading an article. I guess there’s two main form languages in the world right now. One is Apple, and before it Dieter Rams, Braun and so on if you know your design history. Then the other is what came out of the international style in the 20s and 30s from the US in the architecture world, and my dad for some reason picked it up and turned it into product design.

They’re the two main styles in product design, and then you have all the nothing design that doesn’t really have character. What we’ve done here for 54 years is we’ve found a tune that we like and other people like and we’re still playing those instruments.

With new technology arriving it gives you more freedom but that clear, cool look is just in our genes. You play classical or rock or whatever, and we play this style of music. That’s just how we like things to look.

You’ve said that there is no longer really such a thing as Scandinavian design, European design and so on. But these notions existed as you were growing up, so do you still feel your output as a designer has been influenced by such stereotypes?

I think that the notion of this ‘Scandinavian design’ that I don’t think exists comes from democracy and the welfare system, because society knows that if you want to have a good society everyone in it has to have a good life.

We’ve had democracy for a long time and the women got the vote in 1915. We knew if everyone wanted to be on board the welfare ship of a good life, everyone has to be respected. There’s a Danish saying: If you speak to the King in a man, you’ll get the answer from the King. If you speak to the bastard in a man, you’ll get the answer from the bastard.

There’s a long tradition of making life good, not just for education and medical care, but also giving people good products and cosy homes. There’s a long tradition in this part of the world and maybe it’s more developed than in Morocco or Turkey where they had other agendas.

Good design has come out of Scandinavia because we’ve had the welfare system so long. There are other theories that it’s so hard living here that you have to get the most out of the material but those days are long gone.

There’s a consciousness that we can’t just live from our hands but from what’s inside our brains. And the new idea is what’s going to move us forward as a species. A creative industry is stimulated in this art of the world maybe more than others. That’s my assumption.

It’s a big mix of a lot of things. There’s no lack of resources here, but there was once. A consistent design focus has probably been longer in northern Europe in modern times than in other parts of the world where they have other focuses. The Danes use more candlelights than any other nation per capita. In my studio, every day, I have a candle lit. We light them 365 days of the year. When I get up in the morning I light 10 candles in my house, so when my daughters come down it’s nice and cosy.

The studio has created over 700 products for a truly staggering variety of markets, ranging from kitchens, electric bikes and watches to coffins, weather machines and dental equipment. Is there anything you’ve yet to work on that you’d love to get involved with, and do you think there are any products that you’d never get involved with as they are not ‘designable’?

It’s always interesting to design something that you haven’t worked on before. It’s nice and interesting to be involved in new industries because it’s not just the product design, but also the branding, the marketing, the communication. I always find it very interesting, like the coffin, which was so new to us and mind-blowing and scary.

I think everything can be improved that was designed by mankind. You can take a piece of music by Bach and that can probably not be improved. Is that design? I guess it is, because it’s a result of a human brain’s processes.

Echoes by Pink Floyd could probably not be done better. A stone axe from the stone age, could that be done better, more beautifully? Probably not. But I think all the modern things we have around us, of course we could do them better.

I’m certain that man can be improved, mankind. I’m convinced in the next 50-100 years we can design better people. People with more joy, more surrealism, more loving.

There tends to be a thought, certainly in the western world, that mankind is sacred, that it so unique, that we can’t be improved. That’s Mickey Mouse. There’s a Chinese saying that the only thing that’s constant is change and the only thing you can count on is that you can’t count on anything.

You’ve said previously that one of the occupations you could see yourself doing if you weren’t in design would be classical conductor. Is their an inherent link between the arts where a passion for one usually leads to a passion for another?

When you live in a world, being a designer, working with developing news things, to be successful, or lucky as we say in Denmark, you have to be open-minded and sense well. If you sense well, not just products, solutions, designs, whatever, you sense everything stronger. I know from my own life I sense more than I think and therefore I sense good food or beauty, music. I love PF and Bach. Is that a general thing for designers, I don’t know – but I know I could never make a living as a musician cos I always get it wrong.

Does it add to the experience by working on something you love – being a music fan and designing a stereo, for example – or can it cloud your design instincts?

In terms of audio equipment and music, they are so far away from each other, so abstract, that it doesn’t affect anything. But I cook everyday, I love cooking, and I think I’d be better at designing kitchen utensils as a hobby chef than if I’d never cooked. If you’re a pro cyclist you’d know more about how to design a bike than if you’d never been on one.

You designed a Bluetooth headset for Jabra handset that market experts thought wouldn’t sell well when, in fact, it did. There are likely even more examples of products expected to be big sellers that have flopped.. So do you think we should take market research / prior examples with a pinch of salt when designing and stick to our ideas?

One of the main successes in a good piece of music is that the person wrote it with heart. A component in making a successful product is the person or people who created that product. I don’t believe in market research, you have to do your best and know there’s a need for this kind of product at this price point, in this market and so on, but then you have to hope.

I see them more as crutches for marketing people who say ‘well we did market research that said it would sell so many units, so it’s not our fault it failed’. Nobody thought that we’d be successful (with the Jabra headset), and nor did we, with a £100 piece of plastic that weighed 14 grams, and it sold in the millions because the design was right, the technology was right, the timing was right, the communication was right, whatever.

In the 90s, Apple went to Microsoft to borrow money because otherwise they would go bust. No one would have anticipated they’d be in the position they’re in now. You can’t.

When (Sony co-chairman) Akio Morita introduced the Walkman, I guarantee there would have been people in the team that said ‘no one wants to walk down the street with music, or sit on the bus with music, it’s insane!’. But he believed, he ran with it, and it changed the world. You have to believe in something and some ideas fly and some don’t. You can’t analyse. You do your best, then you hope!

Your products always look thought out, structured and rational, yet you’ve emphasised the importance of getting the emotional in too. How do you suggest designers combine both aspects in their work?

We design things as we’d like them to be. Some products we’ll build 75 3D models, and as long as we feel we can improve the quality, the material, whatever, we will, until as a team we say ‘can anyone think how we can make this better, more beautiful?’, and if not, then we’re done.

If we like it and it’s important to us, and honest to us, then chances are someone else out there will like it. We’re far more emotional than analytic here.

My father designed the old Rosti Margrethe bowl and the team did the new one; there’s 50 years between them and the first is probably the most successful bowl in history, selling over 40 million pieces.

The same client called us 50 years later and asked us to make a new one and we humbly said yes, but we knew that would be extremely difficult. It’s like is someone called you and asked you to design a new logo for Coca Cola – you don’t even know if the logo is good or not because it’s been there for 100 years and that’s it.

So we tried to go all different ways with that bowl. After 50 models we said ‘we think the right track here is to improve on the old bowl what can be improved, and let remain that which can’t. So we said ‘ok, what about the spout’. Yes, because there were some problems with that. ‘What about the handle’, and so on.

Interview by Nick Capehorn